July the 4th marks America’s birthday, so we thought we’d take a closer look at one of the principle founding documents, the Declaration of Independence. Written primarily by President Thomas Jefferson, the DOI includes language woven into the fabric of American political mythology despite the fact that the text holds no legal weight whatsoever. For instance, the phrase, “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” appears in the Declaration, not the Constitution of 1789. This common misconception illustrates the power of the printed word; that simple phrase still resonates in modern society because it captures the essence of American ideals.

The First Printing of the Declaration

History classes naturally focus on the tumultuous events surrounding the Declaration’s publication, but the lessons usually overlook the importance of printing during the Revolutionary War era. Jefferson finalized his Composition Draft of the infamous letter to King George on July 2nd, 1776, but the Second Continental Congress didn’t approve it until the 4th of July. The actual signing took place approximately 1 month later. After ratification, the delegates’ first priority was distribution.

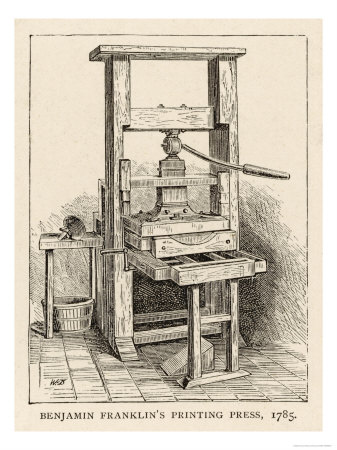

In the late 18th century, printing served as the main vehicle for mass communication. In that respect, John Dunplap, a Philadelphia printer, stands as an unsung hero of our nation’s Independence. Dunplap printed fast reproductions known as the “Dunlap broadsides.” Broadsides are large sheets of paper printed on only 1 side. Broadsides often featured advertisements, wanted posters, event announcements, and proclamations. They were designed to be temporary, throw away items. Dunlap reportedly produced 200 copies of the Declaration overnight on July 4th under the watchful eye of Benjamin Franklin, a man hailed as the greatest printer of his time. Dunlap undoubtedly felt considerable pressure as his actions constituted sedition, a high crime similar to treason. They wrapped up the project by morning, and the broadsides made their way through the rest of the colonies over the course of two days. Upon arrival, printers in the other states immediately hit the presses to publish more broadsides and newspaper articles. One broadside copy fell into the hands of George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army; Washington insisted on reading the document to his troops. According to legend, the crowd cheered with Revolutionary zeal before toppling a statue of King George III.

The Second Signed Print

Dunlap’s broadsides were printed on ordinary paper, but the infamous signed copy of the Declaration in the National Archives was engrossed on parchment. At that time, legal documents appeared on parchment or animal skin for preservation purposes. By 1820, the original ink faded considerably. President John Quincy Adams called on professional printer William Stone to engrave the engrossed document through copperplate and wet ink transfer. Stone’s engraving survived the rest of the 19th century in better shape than the original, and most contemporary reproductions come from his work. The original print still exists, although it was re-encased in 2001 using titanium, aluminum, and inert argon.